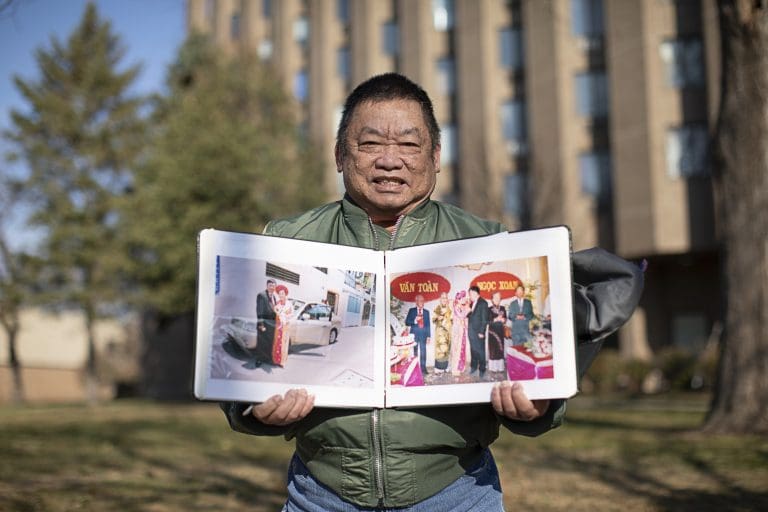

During his 35 years living in Minnesota, Toan worked his way from grocery store employee, to dishwasher, to chef, to three-time restaurant owner — but applying for U.S. citizenship hadn’t been on his to-do list.

“I was busy working, very busy,” Toan says. “I also thought if I had not done anything wrong, or committed any crimes, I didn’t have to be afraid that I would be deported back to Vietnam.”

Toan had been a familiar face at the Institute as he often brought Vietnamese neighbors to the building for assistance with citizenship applications, but Toan wasn’t ready for that step himself.

His wife Xoan became a citizen with the Institute’s assistance, but despite frequent prodding, she had been unsuccessful in convincing her husband to follow in her footsteps. Friends also tried to persuade him, but he remained reluctant. “I feel that I meet my responsibilities, I worked hard for many years, and I pay my taxes,” Toan explains. “I paid into Social Security, and I know I have enough Social Security to take care of me when I got old. But then I met Natasha. She really encouraged me.”

Natasha, an immigration counselor at the Institute, had been assisting Toan with his green card renewal and noted that he was eligible to apply for citizenship. “I really don’t know what I said that changed his mind,” she recalls. “I pointed out that he’s not a citizen, but he’s helping so many people become citizens. He is part of this community, and maybe he realizes he can lead by example. Or maybe it’s just because every time we see one another, we giggle together.”

Whatever it was, Natasha’s message got through, and Toan made the decision to apply. “My main reason was to vote,” he says, “and to contribute to my community in some way.”

Toan came to the United States as a refugee in 1984. As a helicopter pilot with the Vietnamese Air Force, Toan worked alongside the U.S. military, and when the war ended in 1975, he was imprisoned in Vietnam for more than three years. In 1983, he fled by boat to a refugee camp in Indonesia and was later allowed to enter the U.S.

“When I fled Vietnam, I did not have money to bring my family,” Toan shares. “Even though life here was hard, I accepted that. It wasn’t as hard as being in a communist prison.” Later, Toan was able to bring his wife and daughter to Minnesota as well.

Due to his age and length of time with a green card, Toan qualified for an English exemption during his citizenship interview, but his Vietnamese interpreter was unable to get a word in. “Because of the military terms that I used to talk about my service with the Vietnamese Air Force, I thought even the interpreter didn’t understand. I ended up taking the test in English anyway,” he explains. The USCIS officer recommended Toan for approval on the spot and thanked him for his service.

After taking his citizenship oath two weeks later, Toan bought a ticket to Vietnam to celebrate.

“It was the first time I visited with my U.S. citizenship. I felt more stable,” he shares. “I felt that the United States would protect me if something went wrong over there.”

Today, Toan continues to help other New Americans become citizens, but now as someone who has gone through the process himself. “I encourage them to become a U.S. citizen to be able to obtain a better job and to have better benefits,” he says. On Nov. 3, 2020, Toan was also able to vote for the first time.

“I feel happy,” Toan says of becoming a new citizen. “I think people look at you a little differently. My friends stopped criticizing me. And now I don’t have to hear from my wife about this every night!”

Toan was featured in the Institute’s 2020 Annual Report.