The work place is no different from the rest of the world. Cultural and linguistic differences exist and can significantly impact employee expectations, job performance, and outcomes. Hiring and managing a workforce that includes people from diverse cultural backgrounds (with limited English) can successfully meet the labor needs of many organizations and businesses. However, new challenges then emerge and must be resolved. Managers and supervisors must recognize that cultural and language barriers result because workplace “assumptions” are not equally shared, and sometimes even the simplest communication can be misunderstood or misinterpreted.

For example, a new employee from Guatemala working as a hotel room cleaner may initially find many job tasks, conversations with co-workers, or instructions from a supervisor to be confusing, frightening, and seemingly impossible to understand. As a result, her job performance may be lacking even though her motivation is high and she feels she is doing a good job based upon her understanding of the instructions. Supportive supervisors and co-workers can establish an environment where success is defined not only by achieving workplace goals but also by developing cross-cultural communication and skills which lead to the improvement of everyone’s productivity.

Cross-cultural communication and understanding take extra time and energy, which are difficult to find in a busy workplace. However, the benefit is worth the investment. Frequently, the most successful employers are not cultural experts but are those who establish trusting relationships with their employees based on consensus and an exchange of needs and desired outcomes. Solutions to cultural conflicts or misunderstandings in the workplace can most often be resolved by finding a “middle ground” where neither the employer’s workplace goals nor the employee’s cultural identity is compromised.

The following story is an example of how an employee and employer worked together to solve a workplace problem which arose from a language barrier. It is a true story, recounted by a student in the International Institute’s English for Work program.

When the student reported to his part-time janitorial job at the office he was scheduled to clean, he found a cart filled with office supplies, topped with a note: “Dear Janitor, Everything on this cart is garbage and must be thrown away. Please dispose of it immediately.”

The student understood most of the note, but he was reluctant to trust his understanding because the request seemed so odd. He called his supervisor and read the note over the phone. The supervisor told him to follow the instructions on the note. So the employee dutifully threw away pens, pencils, documents and even a computer. He kept a copy of the note.

The next day, the office manager called the student to say that there was a problem: one employee was missing a computer and other important supplies and documents. The student agreed to come in and discuss the problem. He brought the note with him. The manager read the note and told the student that he had done the right thing. The student left the meeting, very relieved.

It was subsequently discovered that an employee had written the note as a practical joke on a colleague. He had assumed that the Russian-speaking janitor would not be able to read the note, and the next day his colleague would arrive to see the contents of his desk marked for destruction. The employee who wrote the note was fired immediately, and the student, in telling the story to his class, finished by saying, “He didn’t know I take English for Work class.”

Communication is only one cause of confusion in a multi-cultural workplace. The following material addresses some issues that are frequently mentioned by employers as areas of cross-cultural confusion or misunderstanding. There are no easy answers. The responses provided are intended to improve awareness of potential solutions. Cross-cultural communication and problem-solving skills must be developed over time and in partnership with non-native speaking employees. Often the best results occur when one has an open mind, plenty of patience, and a willingness to encounter cross-cultural situations as both a student and a teacher.

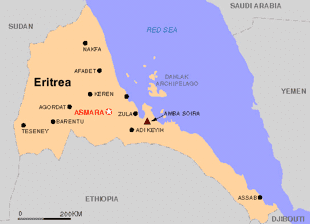

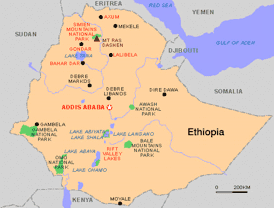

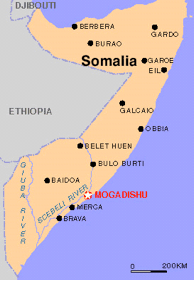

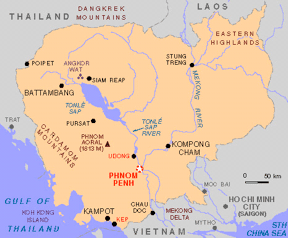

Country Profile

Country Profile

Country Profile

Country Profile Country Profile

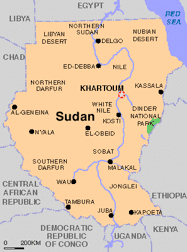

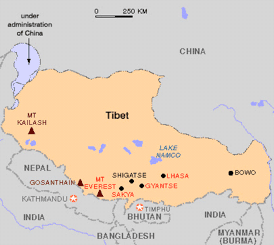

Country Profile Sudan is geographically the largest nation in Africa. It’s a population of 39 million citizens that live in a land divided by religion, war and poverty. The government of Sudan and the northern two-thirds of the country are controlled by ethnic Arabs committed to making Sudan an Islamic state. The southern one-third of Sudan is made up of Africans of various ethnic tribes and religious beliefs that have fiercely resisted cultural and religious domination.

Sudan is geographically the largest nation in Africa. It’s a population of 39 million citizens that live in a land divided by religion, war and poverty. The government of Sudan and the northern two-thirds of the country are controlled by ethnic Arabs committed to making Sudan an Islamic state. The southern one-third of Sudan is made up of Africans of various ethnic tribes and religious beliefs that have fiercely resisted cultural and religious domination. Country Profile

Country Profile Country Profile

Country Profile Country Profile

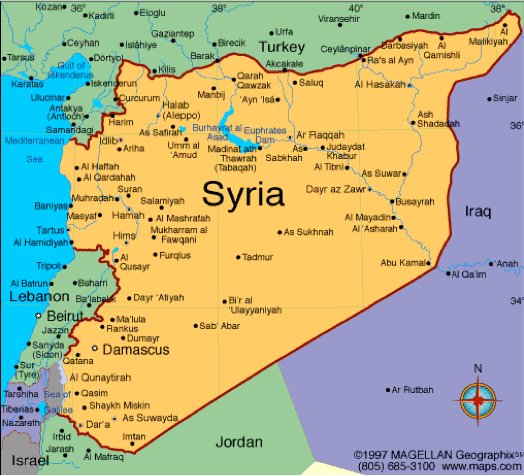

Country Profile Country Profile

Country Profile Country Profile

Country Profile Country Profile

Country Profile Country Profile

Country Profile Country Profile

Country Profile Country Profile

Country Profile Country Profiles

Country Profiles Country Profile

Country Profile